HE UPSET THE RANKS

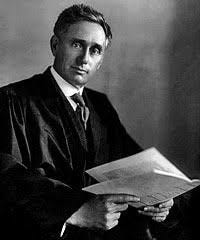

Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice

109 years ago on January 28, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson nominated Louis Dembitz Brandeis to fill the Supreme Court associate seat left vacant by the death in office of Joseph Rucker Lamar.

Being Jewish, I was attracted to the story of Louis Brandeis, the first Jew to serve on the Supreme Court.

The nomination surprised the political world. Louis Brandeis was considered the “people’s attorney” and a progressive on matters related to workers’ rights and corporate fairness. The conservative establishment believed that he was a threat to American values. The fact that Brandeis was a Jew was an underlying reason for the opposition as well.

President Wilson had been impressed with Brandeis and especially with his views against corporate monopolies. Several times in the past he had called him into his office for advice on the economy and had unsuccessfully tried to get him a position in his cabinet.

Why Wilson would put himself in a position to have to defend a nomination for the controversial figure of Louis D. Brandeis is still being deliberated. Wilson was nearing the end of his first term as president of the United States; the United States was at war; there was a surge of antisemitism in the country, especially over the lynching of the southern Jewish pencil manufacturer Leo Frank and the continuous rise of the Ku Klux Klan organization. The politics of the times may have had something to do with this. Wilson was about to run for reelection. He had used his power to increase the Democratic number of Senate members to create a majority in the Senate. He was at the end of his term with impending challenges for his office from the Republican William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt of the independent Bull Moose Party. He might have had some interest in courting the Jewish vote by appointing a candidate whose views tended to match his own more egalitarian views.

Reaction to the nomination was immediate. Several senators in the Senate chamber gasped when the nomination was revealed. Only one Republican senator had been consulted ahead of time by the Democratic president, a courtesy that in the past had been extended to all members of the opposition.

The former US president William Howard Taft called the Brandeis nomination “an evil and a disgrace.” Among others who protested the nomination were former presidents of the American Bar Association, the Boston Brahmin business community, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge from Brandeis’s home state of Massachusetts, investment banker J.P. Morgan, and the president of Harvard University.

The Wall Street Journal and New York Times led the press opposition to Brandeis and called Brandeis “a radical.”

To add to the accusations that Brandeis did not represent the establishment was the underlying antisemitic sentiment. The president of the New York Bar Association, a former attorney general under President Taft, attacked Brandeis supporters as “a bunch of Hebrew uplifters.”

Supporters of the nomination included all but one of the Harvard Law School faculty, among them Felix Frankfurter, a professor at Harvard who would later become a justice himself, Walter Lippman (editor of the liberal New Republic and Harper’s Weekly magazines), many prominent members of the Jewish community including Jewish financier Jacob Schiff and Nathan Strauss, the founder of the Macy’s chain of department stores, Henry Morgenthau, Sr. (former ambassador of the US to the Ottoman Empire), and the leader of the Jewish community at the time, Rabbi Stephen Wise.

Brandeis was a secular Jew raised by immigrant parents who had arrived in America in 1848 from Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) to escape antisemitic laws established after they took the losing rebels’ side in the Prague Revolutionary War. They were also seeking economic opportunities that Brandeis’s father saw possible in America. When they immigrated to America, several of the members of their extended family came too including Brandeis’s future wife, Alice Goldmark, a second cousin. Brandeis’s parents’ Bohemian history went back to the 1500s. Both of Brandeis’s parents’ families had been elite members of a European countercultural movement that was disdained by the traditional Jewish community. They did not attend religious services or observe Jewish holidays. When they immigrated to America, most of the family retained their secular identity. They celebrated the American holidays including Christmas and continued their separation from the Jewish mainstream except for maintaining a close relationship with Brandeis’s maternal uncle, Lewis Dembitz, a lawyer and a Zionist who continued to practice his Jewish religion and was highly influential in Brandeis’s life. Dembitz had been one of three Jewish members to have served at the Republican Convention of 1860 that nominated Abraham Lincoln to office. In honor of his uncle, Brandeis changed his middle name from David to Dembitz when he was thirteen years old.

Brandeis’s family settled first in Indiana, and then in Louisville, Kentucky where Brandeis and his three older siblings attended public school. Adolph, his father, made a comfortable living as a grain merchant. Fredericka, his mother stressed her humanitarian beliefs when raising her children. The family did move around while Louis was growing up. When the Civil War started, they moved to Indiana because of their abolitionist views. After the war they returned to Louisville. In 1872 Louis’s father moved the family to Europe when America’s economy experienced a downturn. Louis began his higher education years while residing in Europe.

After three years touring Europe, the family returned to Louisville, and, at the age of eighteen, Brandeis entered Harvard Law School. He graduated at the top of his class when he turned twenty.

Once he was out of school he and a friend from law school began a Boston law firm that became well known for its activism in civil rights. He acquired the name “the peoples’ attorney” for his involvement in social justice movements and his representation of workers’ interests. In 1908 during the time of the case of Mullen v. Oregon, he created what became a legal approach in the court system titled the “Brandeis Brief,” in which he employed extensive empirical data to make the case for restricting the hours of labor for women and where he did not just rely on arguments that discussed passed decisions and interpretations of the text of the constitution. Since that time, expert testimony and economic and social evidence are now permissible along with legal precedents when a prosecutor or a defender is arguing before the court.

Well, it wasn’t easy to get Brandeis approved. It took four grueling months of testimony before Brandeis was sworn in. By many it was called one of the bitterest contests ever waged against a presidential nominee.

For the nomination to be approved Wilson needed the advice and consent of the Senate which involved a process of sending the nomination for review to the Senate judiciary committee. This action in the past had been a perfunctory task that had usually been done quickly behind closed doors, but that did not happen this time. A special judicial subcommittee was appointed and chaired by William E. Chilton, a Democrat, and comprised of two other Democrats and two Republicans. For the first time since 1828 public hearings were held to assess whether the nomination should be approved.

The opposition pointed to twelve specific allegations intended to attack Brandeis’s character rather than his legal qualifications. Several prominent witnesses were brought in to testify that Louis Brandeis was unfit to serve on the court. They cited cases that involved Brandeis and that were intended to show that he was unprofessional, unethical, unfit in character, and an activist incapable of being an impartial justice.

Supporters called these attacks unfounded and lodged by “privileged interests.” One testimony before the judiciary subcommittee in support of Brandeis was given by Roscoe Pound, the Dean of Harvard Law School, in which he stated that “Brandeis was one of the great lawyers and that he would one day rank with the best who sat upon the bench of the Supreme Court.”

Louis Brandeis refused to testify although he did provide materials and actions to help win favor. In Brandeis’s mind, the fact that he was a Jew was never of consequence.

On April 3, 1916, the judiciary subcommittee voted 3 to 2 along strict party lines in favor of confirmation.

In May, before the full judiciary committee was to meet, President Wilson spoke about Brandeis. “No one is more imbued to the very heart of our American ideals of justice and equality of opportunity …he is a friend of us just men and a lover of the right; and he knows more than how to talk about the rights--he knows how to set it forward in the face of the enemies.” On May 24, 1916, the full judiciary committee approved the nomination along party lines 10 to 8.

Finally, on June 1,1916 the Senate confirmed the nomination of Louis Dembitz Brandeis by a vote of 47 to 22. The vote was taken in the Senate without debate. 27 Senators were absent – for and against were “paired” in their absences. Three Republican senators voted in support of confirming Louis Brandeis, all staunch political progressives. One Democrat voted against the nomination who characterized Brandeis as a talented “publicist and propagandist.”

On June 5, 1916, Louis Dembitz Brandeis, the first Jewish member of the Supreme Court was sworn in at the White House in a room filled with supporters. Said President Wilson: “I never signed any commission with such satisfaction as I signed this.”

Commenting on the day of Brandeis’s swearing in was a Kentucky newspaper that wrote: “Brandeis has the temperament of a crusader rather than of the judge.... we are not worried over that. A little adaptability is only a sideline of Louis Brandeis’s brilliant mentality and boundless capacity.”

Louis Brandeis was a member of the Supreme Court from 1916 to 1939. In the twenty-three years that Brandeis served, he was involved in many important decisions particularly in the areas of free speech, civil rights, and women’s and workers’ rights. Sometimes he won and sometimes he lost but he always stayed true to his values and principles of an open and robust inquiry, a reverence for learning and service to others.

SOURCES:

“On This Day: The Anniversary of Brandeis’s Supreme Court Nomination.” National Constitution Center. January 28, 2024.

“Research into the origins and migrations of the Jewish People. By Randy Schoenberg. Avotaynu. May 3, 2016.

“The Life of the First Jewish US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis.” By Elliot Klaymer. Kesher Journal. July 4, 2010.

“Louis Brandeis Confirmation.” “Louis Brandeis: Family Roots. Wikipedia.

“The Appointment of Louis Dembitz Brandies, First Jewish Justice on the Supreme Court.” By David G. Dalin. Brandeis University. April 2019.

“Celebrating Louis Brandeis’s ascension to the Court__100 years after.” By Julian Cardillo. Brandeis University. June 2016.

“Our Namesake: Louis D. Brandeis.” Brandeis University.

“Louis D. Brandeis (1856 to 1941).” Jewish Virtual Library.

“Louis D. Brandeis: American Prophet by Jeffrey Rosen.” By Courtney Naliboff. reformjudaism.org.

“The Jew.” By Henderson Gleaner. Hopkinsville Kentuckian. February 1916.

“Brandeis Secures Senate Approval.” Marshall Town Iowa Evening Times Republican. June 2, 1916.

“Louis D. Brandeis: Topics in Chronology America.” Library of Congress Research Guide.

“Louis Brandeis.” By Mary Welek Atwell. Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. August 2025.

“A Timeline of Louis D. Brandeis’s confirmation Part 2.” https://brandeiswatch.wordpress.com

A very informative and interesting article that I learned a lot from. Thanks Mimi for all the research you do & then the sharing of this information through your articles.💕